We are in full swing on Rodeo (aka STILL untitled Yellowstone project), and I’m not saying this is my new look now, but I’m NOT not saying that either—

Production offices are online, locations are being identified, casting is underway…

A massive, massive show is slowly finding its footing, getting up on its feet, and that includes all the scripts to make the show go. It’s easy to forget sometimes that there would be no show at all without the daily work we’re doing in the writer’s room. All these things are happening because of the things we’re creating.

Yesterday, I wrapped up the first draft of my assigned script.

After weeks of breaking story, big/small cards, outlines, etc., I actually have a script in hand that should go to the studio and the network next week.

It would be easy to say it’s somewhat anti-climatic; after all, some version of what I’ve scripted has already been read, vetted, dissected. But still…still…there’s something magical about seeing it as a full script; there’s something mysterious about the way the words look different on that kind of page.

Any script is kind of an alchemy; a secret language with rules all its own, more aking to an incantation or spell—

Admittedly though, “script language” is not something that comes super natural to me, or at least, it didn’t. The main tool we use, that pretty much the whole industry uses, is Final Draft. It’s a behemoth, a do-everything scripting program (kind of like the Pro Tools of DAWs, for those that understand the reference) that is extremely powerful at the cost of some intuitiveness and ease of use. There are alternatives, of course, some of which seem really great (including Highland Pro and Fade In), but I haven’t had the time to learn them as well as Final Draft, which is saying something, since I barely know how to use that, either.

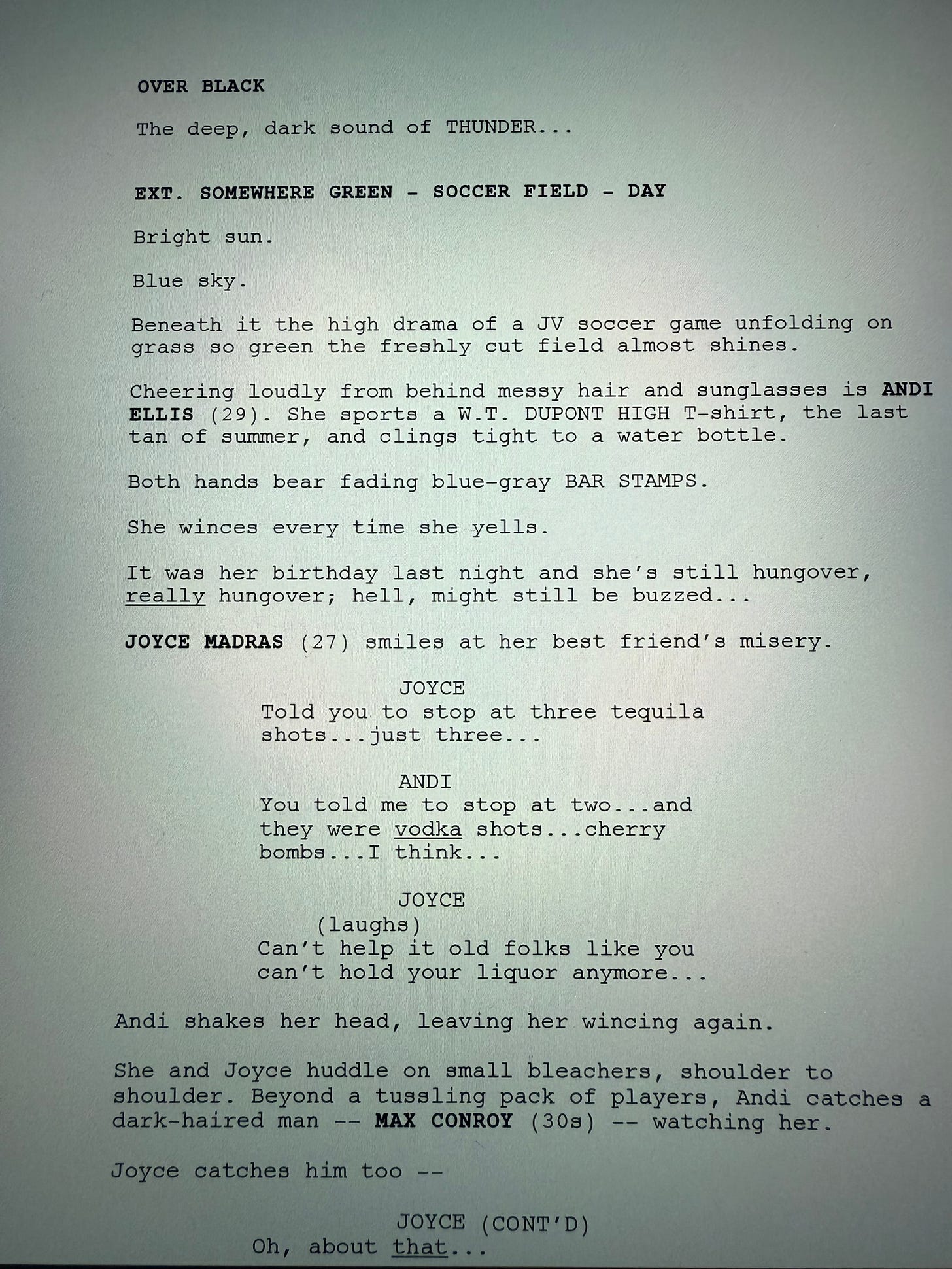

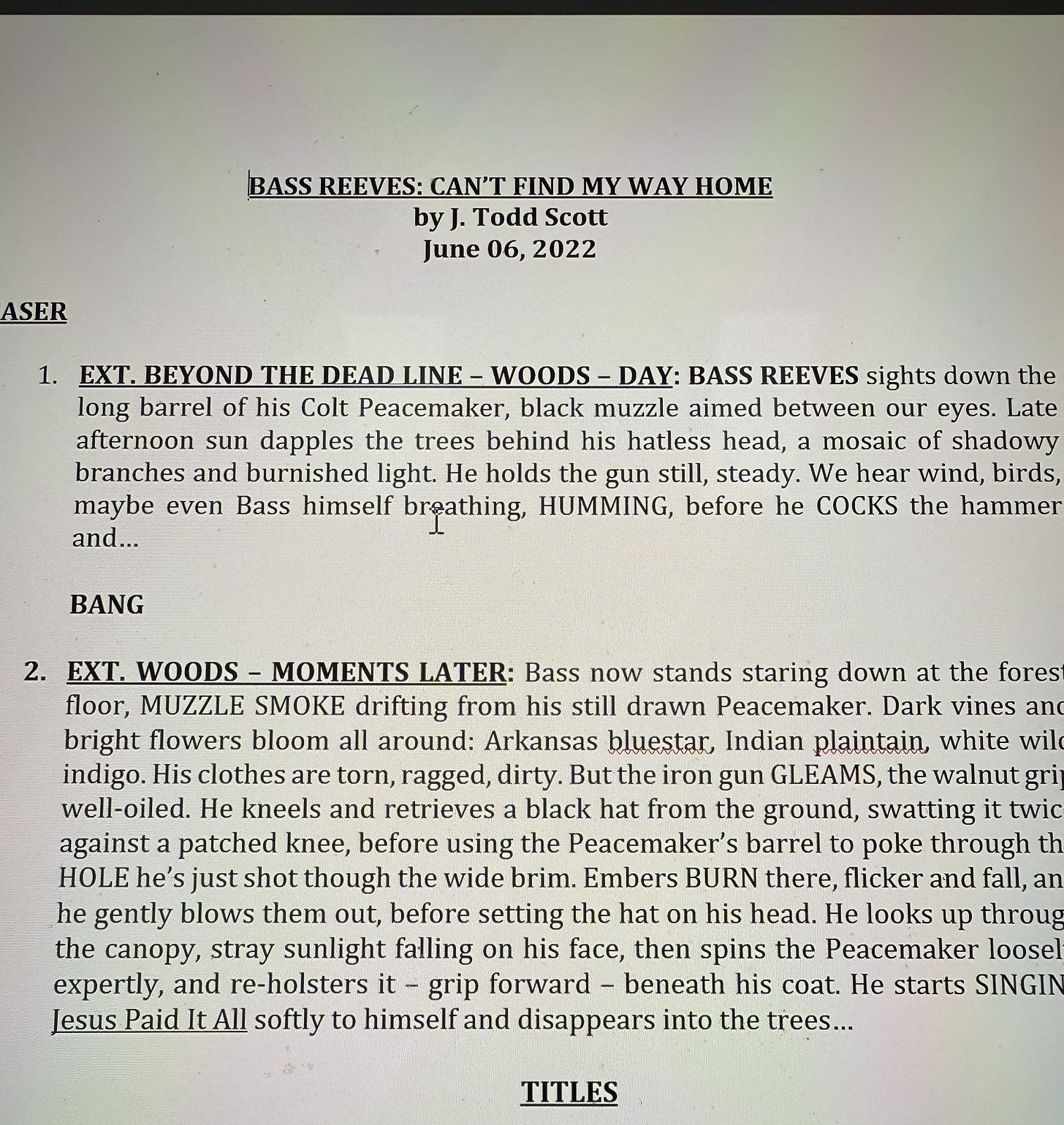

When I started Rodeo and was asked to do step-outs (a quick draft of a scene for the room to review), I had a tendency to default to writing narrative prose in Microsoft Word, basically something much closer to the detailed outlines we also do for the show, and that I got comfortable with on Bass Reeves—

As you can tell from this old Bass outline, they are pretty damn detailed, and although this snippet doesn’t include actual dialogue, they often do. The idea here is it should be relatively easy to take an outline like this, or a similar, smaller step-out, and turn it into the full script or a scene for the script.

You can clearly see the bones of the screenplay it will become.

Bu now, after weeks of writing step-outs and outlines for Rodeo, I’m far more comfortable just taking my prose and going right to script, diving right into Final Draft, without the intermediate step of a few prose paragrpahs. Similarly, when it was time for me to turn my outline for Episode 103 into a script, it was an easier transition.

That time while you’re scripting is where the fun and the art and creativity comes in, where you “find on the page” (hopefully) all the addional great dialogue and imagery that truly flesh out the story. To put it another way, as long as you color within the lines of the plot and characterizations we’ve created together, you’ve got access alone to the whole palette to work with.

I’m doing an interview today about the upcoming release of Scar the Sky, and I’ll probably run down a bit of that time!

As always, feel free to—

I love getting your insights on stuff like this. You're like the perfect hybrid of wide-eyed newbie and savvy veteran and give us the POV from both.

It's funny after reading Elmore Leonard's biography and his experiences in film it doesn't seem like there's a lot of difference these days between film and TV and it seems like a lot of the weird troubles haven't really changed since Leonard's days either.